Canned hops

The beer can debuted in 1935, when an otherwise obscure brewery from New Jersey — Krueger’s — test-marketed them in Virginia, as far from their home market as possible. Breweries may have been initially reluctant, but the public loved cans — they were an overnight sensation. By the end of that first year, Schlitz (then one of America’s biggest brewers) had their beer in cans and every other brewery quickly followed suit.

The beer can was invented by American Can, who patented “Vinylite,” a plastic lining for cans marketed under the brand name “Keglined.” Over the years, the technology continued to improve, from tin to all-aluminium, from cone tops to flat tops, from clumsy openers to pull tops, yet one seemingly intractable problem remained: metal turbity. That’s the technical term for metal leeching into the beer, and consumers increasingly complained about the tainted metallic flavour in canned beer.

The beer can was invented by American Can, who patented “Vinylite,” a plastic lining for cans marketed under the brand name “Keglined.” Over the years, the technology continued to improve, from tin to all-aluminium, from cone tops to flat tops, from clumsy openers to pull tops, yet one seemingly intractable problem remained: metal turbity. That’s the technical term for metal leeching into the beer, and consumers increasingly complained about the tainted metallic flavour in canned beer.

But then craft beer became popular, and with it better beer evangelists preached that canned beer could never be good. And that remained conventional wisdom for decades, made virtually dogma. During that same time, however, research by the can companies solved the metal turbidity problem. Using an organic polymer — really a water-based epoxy acrylic — that was sprayed inside each can during manufacturing, it could now honestly be said that the beer never touched the metal.

Unfortunately, the only beer in cans was not the type that most beer geeks would willingly quaff. The other great hurdle to getting craft beer in a can was the cost. You could buy a cheap, used bottling line but canning lines were quite massive and very expensive. And the people who made cans were used to selling them to big breweries, and so the minimum run for a can was something on the order of a full railroad car, too many and too expensive for even the biggest microbreweries.

But then the bottom fell out of microbrewing, and by the late-1990s equipment suppliers were also feeling the pinch. Hoping to survive the economic downturn, Canada’s Cask Brewing Systems created an affordable solution. They designed a small manual canning line that was cheaper than the average bottling line and persuaded Ball Corporation (a leading can manufacturer) to significantly reduce their minimum orders. All they had to do was convince someone to try canning their beer.

But then the bottom fell out of microbrewing, and by the late-1990s equipment suppliers were also feeling the pinch. Hoping to survive the economic downturn, Canada’s Cask Brewing Systems created an affordable solution. They designed a small manual canning line that was cheaper than the average bottling line and persuaded Ball Corporation (a leading can manufacturer) to significantly reduce their minimum orders. All they had to do was convince someone to try canning their beer.

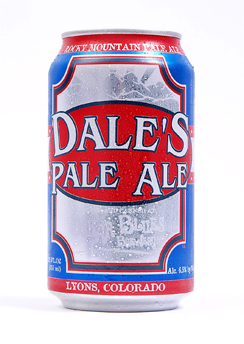

And so Cask started appearing at trade shows and repeatedly sending literature to breweries. When Dale Katechis, of Oskar Blues, in Lyons, Colorado, first read the pitch, he “just laughed and laughed,” thinking there’s “no way this can be done.” But the more he looked into it, the less he laughed. A few months later — in 2002 — Dale’s Pale Ale was released, the first craft beer to be hand-canned. By 2005, Oskar Blues was the biggest brewpub in the U.S. and Dale’s was declared by the New York Times to be the best pale ale in America.

The Oskar Blues team became evangelists for canned beer with the slogan, “the canned-beer apocalypse.” Other small breweries noticed Dale’s success and he was only too happy to show them the light. Today, there are nearly forty craft brewers hand-canning their beer.

The Oskar Blues team became evangelists for canned beer with the slogan, “the canned-beer apocalypse.” Other small breweries noticed Dale’s success and he was only too happy to show them the light. Today, there are nearly forty craft brewers hand-canning their beer.

There are almost as many kinds of beer in cans as there are styles these days, too, from extreme, strong offerings like Surly’s Furious (a 100-IBU Imperial IPA) and Old Chubb (a Scotch Ale) to more unusual beers like Maui Brewing’s CoCoNut Porter and 21st Amendment’s Hell or High Watermelon to lighter lagers like Sly Fox’s Pikeland Pils and Steamwoks Steam Engine Lager. And now that New Belgium Brewing, one of the largest American craft brewers, is canning their popular Fat Tire Amber Ale, expect to see many more beers in cans in the future.

The biggest challenge is unmaking the dogmatic perception of beer in cans as an evil. It’s a persistent prejudice, but is slowly beginning to change as the advantages to canned beer become more widely known. They keep out all UV light, avoiding the skunky taste of clear and green glass. Cans have lower oxygen levels, meaning longer shelf life. They won’t break; they chill faster and can be taken more places, especially where glass is prohibited. And they’re more environmentally friendly, using less packaging plus more of the can is recyclable, with more used in manufacturing recycled cans. Cans are also lighter, resulting in lower transportation costs and fewer fossil fuels needed.

But in the end, the only thing that matters is how the beer tastes. Side-by-side can vs. draft taste tests reveal that it is virtually impossible to tell the difference. That, coupled with the real advantages of the packaging, means that craft beer in cans is where the future of craft beer is heading.

[adrotate group=”1″]

.