Book review: Amber, Gold and Black

The first book I remember reading was called Tip the Dog. It was my Dad’s, and I guess he thought if 1950s three-words-per-page books were good enough for him when he was a nipper, they were good enough for his only son.

It was beautifully illustrated, the front cover gleaming with bright post-war optimism showing a sky so blue, grass so green, and the protagonist, as undogly as this may seem, appearing to smile in mid-air in some incredible feat of dogrobatics, catching a brilliant red ball. Tip was one happy dog.

It was beautifully illustrated, the front cover gleaming with bright post-war optimism showing a sky so blue, grass so green, and the protagonist, as undogly as this may seem, appearing to smile in mid-air in some incredible feat of dogrobatics, catching a brilliant red ball. Tip was one happy dog.

The cover didn’t let me down. The book had page after page of thrilling three-word storyline and superb artwork. And not a vet in sight.

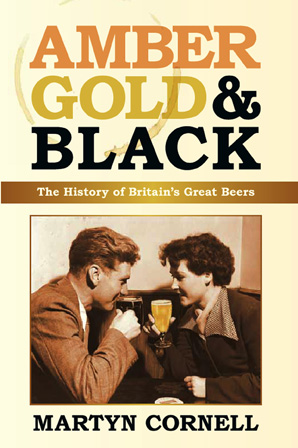

Recently, I stumbled across a new book, Amber, Gold and Black, while browsing the web. I was unsure whether to buy it, because in 2D on a computer screen the front cover looked boring and the title is terrible.

I reasoned that, unlike Tip the Dog, the cover may not do the contents justice.

As for the title, I think the beer-reading public is a little beyond such simple descriptions as amber, gold and black. The grognoscenti are about appreciating subtleties, bouquet, tastes, food-matching, surely.

There are more than three types of beer and connoisseurs of craft, boutique, micro-brewed, artisan, or whatever-you-want-to-call-it beer, know it.

We’ve been reading the BJCP style guide and the blogs and tweets and that bastion of authority the marketing man’s beer bottle label, and we’ve sucked it up and in, and we’ll trap you in a corner and go on about it until your ears bleed if you’re not quick to get away.

We’ve been reading the BJCP style guide and the blogs and tweets and that bastion of authority the marketing man’s beer bottle label, and we’ve sucked it up and in, and we’ll trap you in a corner and go on about it until your ears bleed if you’re not quick to get away.

But the history of British beer is a worthy subject; much we drink today owes a debt to Anglo Saxon experiment. As the cursor hovered over the buy it now symbol I felt the ghostly spirit of the 19th Century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard on my shoulder saying, “life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward.”

And that is why this book is so absolutely brilliantly revelatory.

It’s like watching Mythbusters whilst chroming hops. Ok it’s a little less exciting than that, but you get the picture.

Martyn Cornell, I now know, is a beer writer par excellence, author of Beer: the Story of the Pint, Beer Memorabilia, and a blog. The painstaking research that has gone into this work is phenomenal; presumably it is relieved by regular intake of the subject matter.

I have an image of Martyn in my mind, hunched over desks in a gloomy brewery archive, pint glass in one hand, magnifying glass in the other, checking facts, analysing historical maps, and ultimately un-teasing the threads of history from the inevitable myths of yore.

Amber, Gold and Black features chapters devoted to various beer styles, each tracing obscure intertwining and often complex histories, littered with literary references, recipes, indicators of the original gravities (OG) of each beer discussed and evidence-based claims, often illustrated with period adverts and passages from documents.

It is ‘proper’ history, but about beer.

Each chapter runs more or less chronologically, finishing with nods to the notable examples of current beers in the chapter’s style.

Clearly the book is written for a UK audience, so it helps if you have a reasonable knowledge of UK geography to understand some of the content, or at least a map. But it is accessible and relevant to anyone.

Amber, Gold and Black adds a good handful of isinglass to the stuff I already knew, bringing a new level of clarity to the subject through documents and deduction. But sometimes Martyn plainly rewrites history – correctly.

Here a just a few of the books facts you can quote to an over-enthusiastic beer-obsessive next time you’re having an ear-bleeding competition. In Victorian times there was a Yorkshire ale style called Australian ale, it was a strong, well-aged beer aimed at the colonial market.

Until the end of the Victorian era, Mild “Britain’s most misunderstood beer,” was young (matured for as little as seven days) sweet, sometimes well-hopped beer. It came in a multitude of hues and strengths, rather than the copper to dark brown of today.

Britain had a healthy tradition of brewing wheat beer, an end only coming when a 1697 Act of Parliament introduced tax on malt and insisted it was the only grain to be used in beer.

I could go on forever about this book, so you’ve been warned, if you see me coming you might want to head the other way. Otherwise, you could buy your own copy and correct me when I get things wrong.

And Dad, if you’re reading, you can have Tip the Dog back now.

[Ed: This is definitely a books that belongs on any beer-lover’s bookshelf. It is a must read before anyone tries to explain the history of the IPA. Bookmark Martin’s site too].