A Cold War: The battle of Budweiser

What do Budweiser, VB, Champagne, Byron Bay Pale Lager all have in common?

What they have in common is that they are brands that are named for a region where they originated.

Using regional names in beer branding is pretty common. In Australia, you could fill a fridge with beers that are named for a region: VB (Victoria Bitter), Melbourne Bitter, Carlton Draught, Swan Lager, Matilda Bay, Byron Bay, Gage Roads (named after the straits of water between Rottnest and Fremantle!), Great Northern, Eagle Bay, Cowaramup, McLaren Vale, etc.

Using regional names in beer branding is pretty common. In Australia, you could fill a fridge with beers that are named for a region: VB (Victoria Bitter), Melbourne Bitter, Carlton Draught, Swan Lager, Matilda Bay, Byron Bay, Gage Roads (named after the straits of water between Rottnest and Fremantle!), Great Northern, Eagle Bay, Cowaramup, McLaren Vale, etc.

The problem with regional brands is that sometimes, they can become valuable property, and when there is valuable property shared by multiple members, there’s often a fight not too far away.

The issue becomes particularly pertinent as a regional brand can travel and can become quite disconnected from the region where it originated. Matilda Bay beers are named for a bay on the Swan river in WA but are made in Victoria. Great Northern originated in Cairns, but is now brewed in Yatala (SE Queensland). And Byron Bay Lager is brewed… – well, we were pretty sure it was not Byron Bay as Matt pointed out. That is now confirmed! [Yes, though with the closure of Warnervale, the beer is now brewed at Cascade in Tasmania. Ed.]

The best examples of this battle might be seen in the well-known battles by regional defenders of Budweiser and Champagne contesting the right to limit the use of the brand to output from the region. Champagne won, Budweiser failed! So what is the story of why Budweiser failed – and what does that mean for other regional brands?

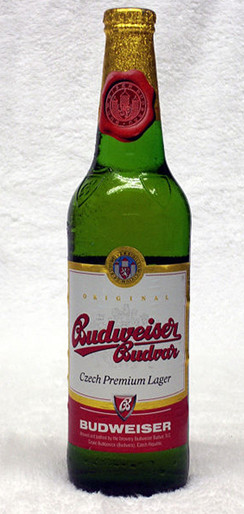

Since 1876, Anhueser-Busch in the US has marketed a beer called Budweiser, but as everyone knows, the original Budweiser comes from the Budvar brewery in the Czech Republic. Or is it! The story is particularly complex and interesting one, so open a beer to suit.

Let me start with some of my own background research into this story. Twenty years ago, in July of 1994, not so long after the fall of the iron curtain and the collapse of the Communist rule in the Czech Republic (1989+), I was invited by some West Aussie buddies to join them on a consulting gig to the Platan Brewery in Protivín.

Now post-iron curtain, few businesses in the Czech Republic had real money to pay real consultants. This is where I came in! Platan Brewery offered to cover my travel to the Czech Republic, and offered me a car, accommodation, food and all the beer I could drink in return for my services. I accepted – and I daresay it was one of the best paid jobs of my life!

One of the big bonuses was that my client was located very close to České Budějovice, a city renowned for being the ancestral home of the original Budweiser. Another bonus was that my client, the CEO at Platan Brewery had been a brewer at Budvar before accepting his management role at Platan.

One of the big bonuses was that my client was located very close to České Budějovice, a city renowned for being the ancestral home of the original Budweiser. Another bonus was that my client, the CEO at Platan Brewery had been a brewer at Budvar before accepting his management role at Platan.

The biggest bonus was one night, we (the Aussie consultants and the client) visited the Budvar brewery. We quickly found our way to a large, heavy wooden table in a room that led out to an impressive array of fermenting vessels. So a couple of Czech brewers and three Aussie beer consultants sat down to talk.

First order of business was to get a beer. One single, enormous 1 litre mug was picked up and we were invited to walk out back and were shown which vessels we would be sampling that night. The single enormous mug was filled and we walked back to the wooden table and got down to the serious business – talking and passing around this litre mug, each taking turns to walk out back and refill it when the need arose.

And what I learned there was fascinating. I note as an aside that it is a testimony to the excellent quality of the beer that I am able to remember what I learned. Any mistakes I make can be attributed to the quantity I consumed.

In 1994, in České Budějovice, there were two breweries: Budvar and Samson (which had two main brands at that time, Samson and Crystal).

In 1994, in České Budějovice, there were two breweries: Budvar and Samson (which had two main brands at that time, Samson and Crystal).

Budvar (the brewery where we were drinking) is the brand that many think of today as the original Budweiser. It certainly is the biggest selling Budweiser today outside Anheuser-Busch’s offering, but this brewery only started operating in 1895. Remember, Anheuser-Busch had been brewing and distributing a beer called Budweiser in the US from 1876.

It is the other brewery, Samson, which claims to be the first to have marketed a beer called Budweiser. The Samson Brewery was originally known by the deliciously mouth-filling name of “Die Budweiser Bräuberechtigten – Bürgerliches Bräuhaus-Gegründet 1795 – Budweis” or “Bürgerliches Bräuhaus Budweis” for short!

Try to say it! As your mouth fills with more foam than a lager freshly poured directly from a fermenting vessel, you might realise it is German. That name translates as the Civic Brewery of Budweis in English. So why the German name?

České Budějovice is located in Bohemia, a region that is today a part of the Czech Republic. However, from 1526 to 1918, the kingdom of Bohemia was located within the Austrian, and later Austro-Hungarian Empire, and therefore German speaking.

You see regions are very confusing. Go grab another beer, and I will explain the convoluted history of the Samson and the birth of Budvar.

The Samson Brewery began life in 1795 (as the Civic Brewhouse Budweis or Bürgerliches Brauhaus Budweis). This is the one that claims to have been the first to have used the Budweiser brand.

By the by, Budweiser is strictly an adjective used to describe something as being of the region Budweis. What’s the difference? Well, imagine how you might feel if someone in the US named a beer ‘Australia’. Now imagine that their label actually said ‘Australian’. The use of the latter, the adjective, could imply a style as in Australian-style or a stronger claim to being from Australia.

However, to add to the complication, Budweis and Budweiser represent the German transliteration of the Czech words for Budějovice (region) and Budějovický (adjective). So? Well imagine how we Aussies would feel about having to suffer everyone telling us that Brisbane ought to be pronounced ‘briz bayn’. Or how the French might feel when we all insist that their capital should be pronounced ‘pa-riss’, not ‘pah-ree’.

The growing Czech speaking population wanted their own beer and one that reflected the Czech name for the area, and in 1895, the Budvar brewery (Budějovický Budvar or Budweiser Budvar in English) was established. Ironically, it was this Czech brewery that was to become the main party battling for the exclusive right to use the German adjective for the region, Budweiser.

In 1918, at the end of WWI, Bohemia became part of Czechoslovakia, and all things German became very unpalatable, and so the Civic Brewhouse Budweis (Bürgerliches Brauhaus Budweis) became the Samson brewery – and the German word, Budweiser, fell into disuse. At the end of the communist era however, the brewery reclaimed their rights to the name Budweiser, and became the Budweiser Citizen’s Brewery carrying both Czech and German names for a while!

In 1918, at the end of WWI, Bohemia became part of Czechoslovakia, and all things German became very unpalatable, and so the Civic Brewhouse Budweis (Bürgerliches Brauhaus Budweis) became the Samson brewery – and the German word, Budweiser, fell into disuse. At the end of the communist era however, the brewery reclaimed their rights to the name Budweiser, and became the Budweiser Citizen’s Brewery carrying both Czech and German names for a while!

Meanwhile, Anheuser-Busch, an American company founded by two German-born men it might be noted, was busy pulling and selling a lot of beer under the name of Budweiser.

Anheuser-Busch claimed the exclusive right to the use of the brand name Budweiser in 1878, about two years after they began marketing the brand. This then constrained the Czech brewers exporting their beers with Budweiser branding into the US, even though Budweiser was a regional name as acknowledged by Adolphus Busch in the NY District Court in 1896.

Sadly, being first and being from the region was not sufficient as reflected by another regional Czech brand. Pilsener (pilsner) or pils originally described beer from the Czech town of Pilsen (Plzeň), but the term is now used generically. For instance, Matilda Bay’s Bohemian Pilsner!

Exclusive rights to a regional name are not automatic; you may well have to fight for them – as the Czechs found out. The Battle of Budweiser became a bar-room brawl that began in earnest from the 1890s onwards.

In 1896, Anheuser-Busch threw a furtive punch by distributing a poster of Custer’s Last Fight to bars to promote their beers. By doing so, they celebrated the year that A-B first started selling their Budweiser (1876, the same year as Custer’s defeat at Little Bighorn) and the launch of Michelob, another brand named after the Czech town of Měcholupy (Michelob in German).

A long and complicated dispute ran into the first forty years of the 1900s. Mostly, it is reported that Anheuser-Busch, Budvar and Samson agreed that Anheuser-Busch could use the name Budweiser in North America (north of Panama), but not in continental Europe, and the Czech brewers could use the Budweiser brands in Europe but not in North America.

Today in North America, Budvar sells its brands as Budvar or Czechvar. Samson sold their brands as B.B. Bürgerbräu into the US. In Europe, both breweries used the regional designation Budweiser in their branding.

The implications of all of this? Regional brands are slippery little suckers.

First regions are sometimes hard pressed to lay exclusive claim to the name itself. Many of Australia’s towns and cities are named for locations in the ‘old world’ or elsewhere, e.g., Perth’s namesake can be found in Scotland. I am writing this while in Coolangatta, QLD which is named after a ship called Coolangatta that wrecked in the area. The schooner was itself named for Coolangatta Mountain near the Shoalhaven river in NSW.

Second, does reference to a region necessarily mean that the product comes from there? India Pale Ale did not come from India, it was sent there! Is it okay to name a brand for some striking regional feature: do you reckon that Uluru red ale might sell?

Third, we’re haggling about brands which are words that marketers want to manipulate. On one hand, the marketers try to press a word into service for some purpose that suits them. Virgin – an airline, a mobile, a credit card or something you might be hard pressed to find in a pub?

And then at other times, admittedly rare, marketers seek to defend the original meaning of a word, namely when it is a region! Consider how the proud Czechs are so intent to defend a German name today when at times in their past, they have sought determinedly to erase it.

Fourth, what’s in a name, just make up a new one! From the shores of Queensland’s Coolangatta, I look out past Palm Beach and Miami (not to be confused with the US versions) to Surfers Paradise, an area originally known as Elston!

And now well over 100 years later, the battle of Budweiser continues with Anheuser-Busch continuing to push for the rights to distribute their version of Budweiser into Europe. In 2012, Samson was bought by Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI, the world’s largest brewer based in Belgium) and in the acquisition, Samson gave up their rights to the Budweiser name.

Anheuser-Busch has tried to acquire the Budvar brewery, but so far, unsuccessfully. However, ABI seem determined and will almost certainly continue trying to get their version of Budweiser into Europe.

I suspect that the David in this mis-matched battle, Budvar, is the big winner. Their continued participation in the dispute is probably great publicity for their beers, and offers a fun way for the Europeans to stick it up the American Goliath.

What’s in a name? You say Budweiser, I say Budějovický! I would hope that in the end, it is a matter of taste. And that the taste is more important than the name.